I’m sure that title caught your attention and maybe this line will too – Liverpool International Music Festival (LIMF), which is the city’s awarding winning music festival that has run annually since 2013, not only reflected The Beatles but also, and perhaps more importantly for this article, exposed some often unrecognised and unknown elements that formed some of The Beatles’ musical story! Now, I’m sure some of you reading this may be thinking ‘How so?’… but stick with me for a while and I will explain.

When it was announced that a new festival, to be titled, Liverpool International Music Festival was going to replace the Mathew Street Festival there was a bit of uproar. Understandably so. Many in Liverpool loved the Mathew Street Festival and it was so entwined with The Beatles (and we know how much we LOVE The Beatles in Liverpool). In fact, the festival started as a stage outside the Cavern in 1993 by the company behind the annual Beatles’ Convention. So The Beatles were intrinsically connected – not only in name and location but so many of the performers were Beatles’ tribute bands. As you know, the festival was a hit and began to attract more and more people each year. As its popularity grew, the celebrations expanded beyond Mathew Street and the festival with multiple stages across the city centre and an estimated 350,000 fans annually – many of whom identified as Beatles’ fans.

However in 2013 the writing was on the wall for a variety of reasons – ranging from major issues around anti-social behaviour to what many in the music sector deemed ‘an outdated reflection of the musical integrity of Liverpool’. So when the city decided to go in another direction with LIMF the naysayers were quick to respond with concerns that the new festival would not be reflective of and nod to The Beatles’ legacy that was so celebrated as part of Mathew Street festival.

As the appointed curator of the festival I didn’t have those same concerns. I was fully aware of the greatness of The Beatles, even though at the time I wouldn’t say I was super knowledgeable about the full breadth of their music or the depth of their story. BUT I knew what they represented for the city and so I was more than ready to reflect that greatness but in a way that would be progressive, a little more nuanced and creative than many people would have expected.

From the start we had a music first, inclusive and entertaining approach, whilst still aiming to be progressive, courageous and avant-garde. These were all principles I believed The Beatles represented and we wanted to also. We also wanted to really hone in on how LIMF could, like The Beatles did, take something that felt uniquely and definitively local but make it resonate globally. That’s what The Beatles done right? – 4 local lads with big personalities and sounds influenced by their locality, communicating it through music to the world! So with LIMF we wanted to do that too. Take our unique vibe, perspective, musical appetite and not only use it to entice and entertain our citizens here but for visitors to the city too.

Nile Rodgers & Chic performing at LIMF in 2019.

Ok back story and basics done, let me get back to the title of this piece. Coming in to LIMF I had some knowledge about The Beatles and their often-undocumented relationship with Black music. The initial information was a result of a short documentary I executively produced under my first company URBEATZ over a decade ago. The short, entitled, ‘L8: A Timepiece’, was about the L8 social clubs but made a light reference to how The Beatles interacted, and some may say, were influenced by the Black music being played in these social clubs in Liverpool 8, as well as by a local Black vocal group called The Chants, who The Beatles were enamoured with and actually backed at the Cavern.

My understanding of this relationship between The Beatles and Black music got even deeper through the process of making a music documentary as part of LIMF 2015. The documentary called ‘Routes Jukebox’ explored the roots and routes of the music and sounds that took Liverpool to the apex of the music world. It told the story of the ever-evolving Liverpool music scene since the 1940s and its influences and connection with other music cities such as New York, Detroit, Nashville and Kingston.

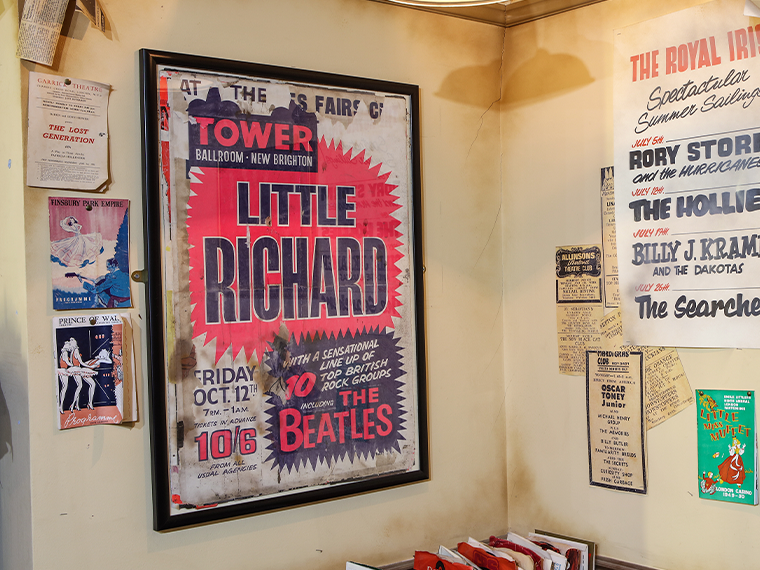

Our starting point was the story of the Cunard line and specifically the ‘Cunard Yanks’, who were merchant seamen from Merseyside who worked as Cunard Line crew on the transatlantic shipping routes from Liverpool to New York from the late 1940s to the 1960s. They are commonly credited with bringing back Black R&B records from the US that influenced the entire Liverpool music scene especially around the beginning and height of the Merseybeat era, and specifically bands like The Beatles’ – informing their soon-to-be-popular musical style and a large part of the group’s early repertoire. This was supported through our findings. However it was also strongly stated that members of the band were also actively seeking out inspiration from Black groups – whether touring from the states (like Little Richard) or local groups (as in the aforementioned The Chants story) – and by attending the L8 Social clubs or other shows led by Black musicians and DJs.

Little Richard poster at The Beatles Story, Liverpool.

After this, we kind of assumed that as we moved forward from the time period and around the world (in the documentary) the relevance of Black music to The Beatles would be less but that was far from what we found. For example, in Detroit we found out that The Beatles were very much connected to Black American soul music, specifically via Motown Records. From speaking to insiders we learnt that The Beatles took a lot from the Motown Sound, covering many songs and emulating vocal delivery styles from the likes of Smokey Robinson. In fact in 1962 they performed 3 covers from Motown Records for BBC Radio and later released 3 covers as part of their second album release, ‘With The Beatles’. Interestingly, the bond between Motown Records – the definitive Black American Soul label – and The Beatles just continued to blossom after that.

But what really blew my mind was when we went to Kingston, Jamaica as part of a thread that was about the presence of Reggae and Ska in Liverpool in the 80s and 90s and how it connected back to the root of it all in the Caribbean What we discovered from music historians and academics in Kingston was that not only did so many Jamaican musicians and artists have tremendous respect for The Beatles but so many Jamaican bands covered the Beatles and vice versa! The Beatles were being influenced by and influencing Black music in Jamaica!

Once the documentary was completed we screened it at various places including the Grammy Museum in LA among other places and we actually received an international film award for Best International Music Documentary. With that said, the proudest moment for both I and the director/producer, Jernice Easthope, was the emotion stirred by people who felt we unearthed stories that had never been told before, especially around The Beatles and Black music.

BUT I’m not finished…

That same year, at LIMF, we partnered with Grammy-winning producer Steve Levine to do a very special ‘Record Producers’ event – which centres around Steve talking with other successful record producers about their careers, their process and the making of hits. This was a unique live show and we were lucky enough to get one of the great songwriters and producers in the history of music (and a staple of the “Motown sound”), Lamont Dozier for this. Lamont further added layers to the stories about Motown and The Beatles by sharing how The Beatles and Brain Epstein really respected their work, the friendly-rivalry between camps and how the sometimes forgotten Supremes album ‘A Bit of Liverpool’ was a dedication to an almost symbiotic relationship developed through the Motown relationship with The Beatles.

In 2020, I curated a spin-off mini-festival called ON RECORD that explored Black music in Liverpool and the role it has played in the city and communities over the past 70 years. As part of that we partnered with National Museums Liverpool to delve even deeper into the influence of Black music on The Beatles in a two-part interview with Mark Lewisohn, the acknowledged world authority on The Beatles. He was joined by representatives of the Liverpool City Region Music Board, Paul Gallagher and Peter Hooton, to discuss the Black artists and Black music genres that inspired the Fab Four. The first of the two-part interview focuses on the early influences of Black music on The Beatles from 1956-1962 and the second focuses on their recording career, 1963 and beyond. This crystallised so much of what I had learnt.

So I hope it all makes sense now – my journey as the LIMF curator has been a tour-de-force in The Beatles – not just about their music and their influence in many ways on Liverpool music to this day and how I could take their principles and infuse them into a contemporary music festival BUT also how their relationship with Black music and culture influenced them, and likewise influenced others and contributed to their unparalleled impact on music across the world!

– Yaw Owusu

Yaw Owusu is a creative consultant specialising in the strategic design, development and delivery of music and music culture projects, programmes and initiatives.